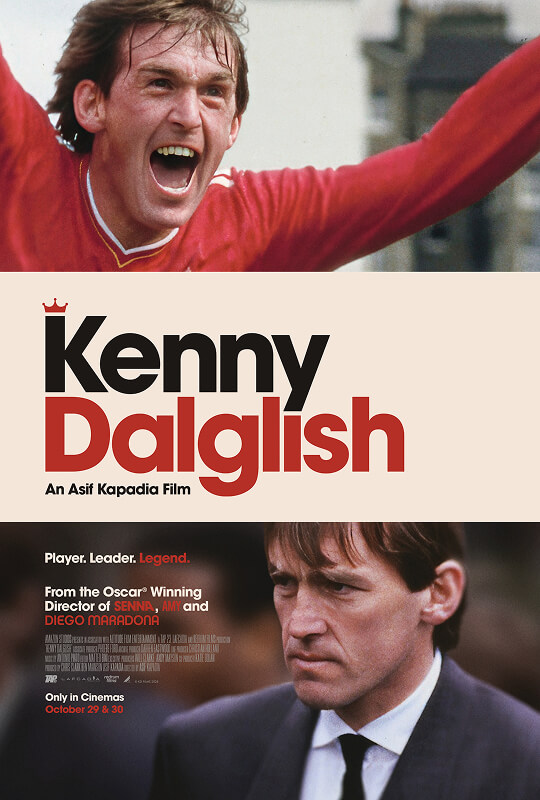

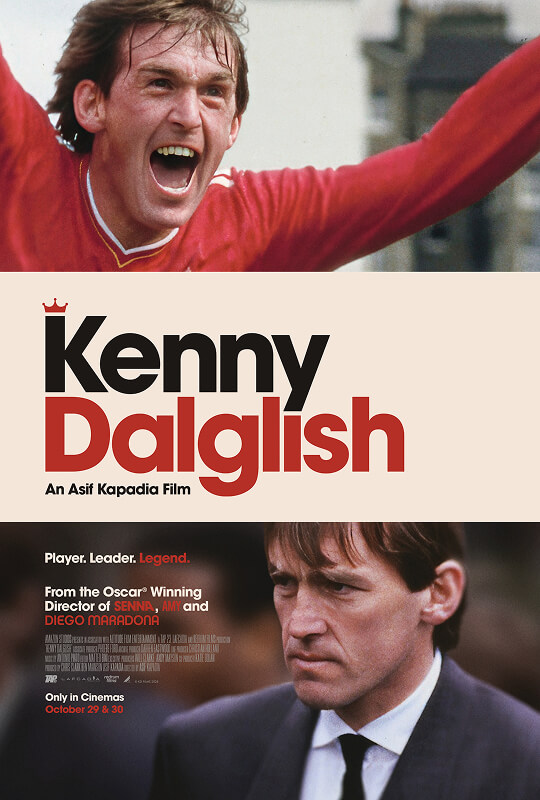

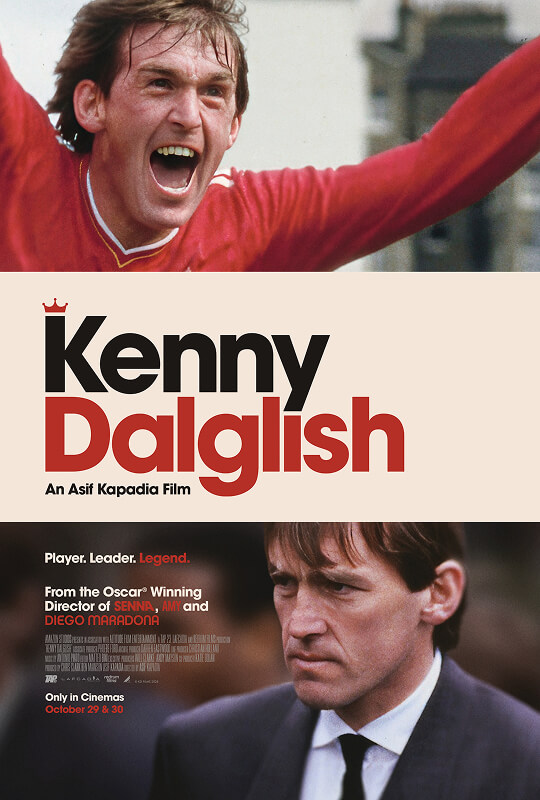

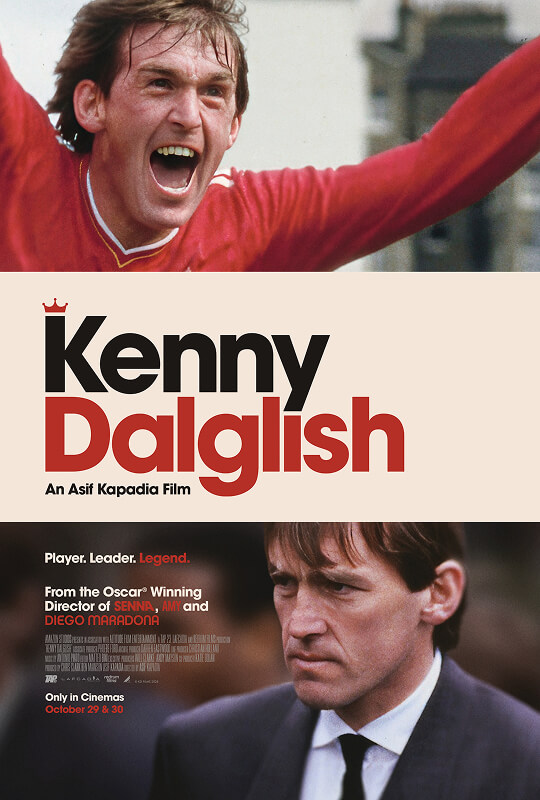

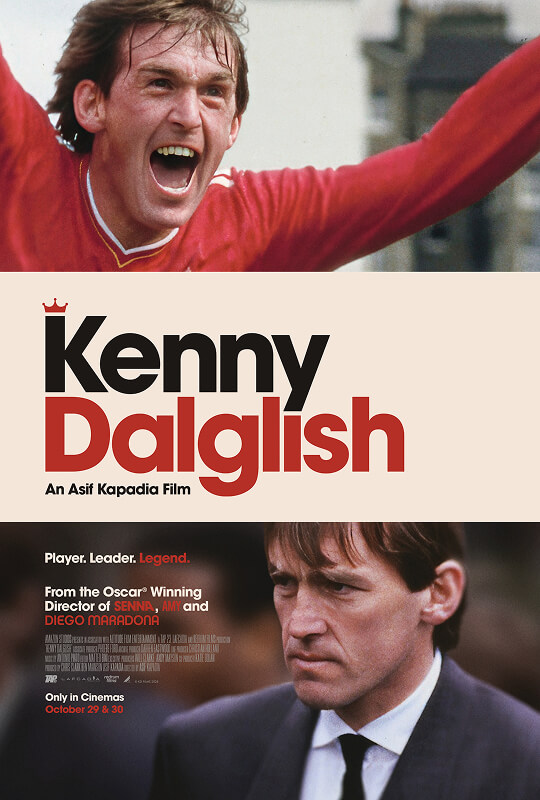

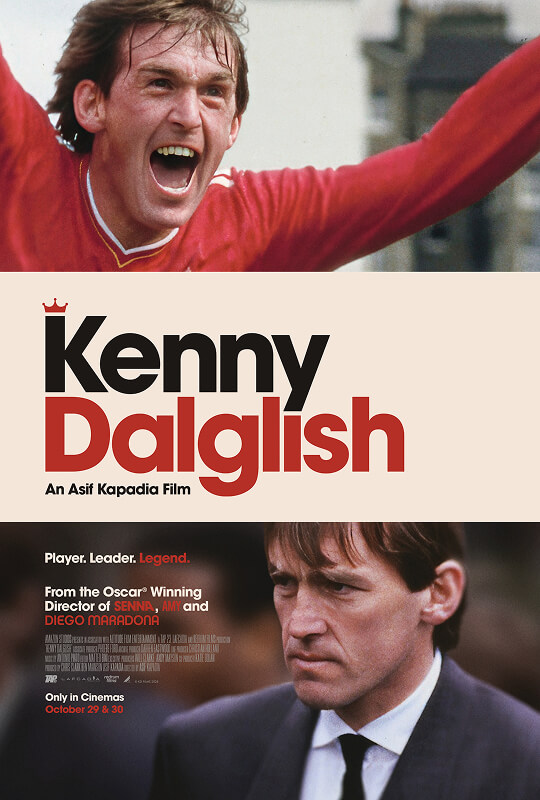

He was Glasgow’s. He is Liverpool’s. Now he can be the world’s. Kenny Dalglish, the captivating new documentary by Asif Kapadia – the Oscar and Bafta-winning director of Senna, Amy and Diego Maradona – introduces the Celtic, Liverpool and Scotland legend to a new audience, telling a story of talent, loyalty and community.

Kapadia relates this tale with his trademark use of archive footage. There are no talking heads or omniscient narrators, with most of the commentary coming from Dalglish himself, his wife Marina or his former Liverpool team-mates Alan Hansen and Graeme Souness. The fresh imagery – and the filmmaker unearthed 100 film reels alone from Dalglish’s Celtic days – makes the past present. Those early Celtic clips show better than any how supremely gifted Dalglish was. His anticipation, feints and touches display a mastery of timing and space; some of his movements resemble Lionel Messi before his time.

The film deals breezily with Dalglish’s childhood, followed by the Celtic era and his first Old Firm goal against Rangers. “That was the big ’un,” he says. “Not because it was a great goal. Because it can set your life up for you.” Life-changing too is his wedding as a Protestant player for a largely Catholic-supported team to his Catholic wife Marina (“the best signing I ever made”). The clips highlight Dalglish the man: his refusal to leave Celtic when manager Jock Stein suffered a car accident, the so-called “Jock Mafia” he formed with Hansen and Souness at Anfield, and Christmas Day with his family.

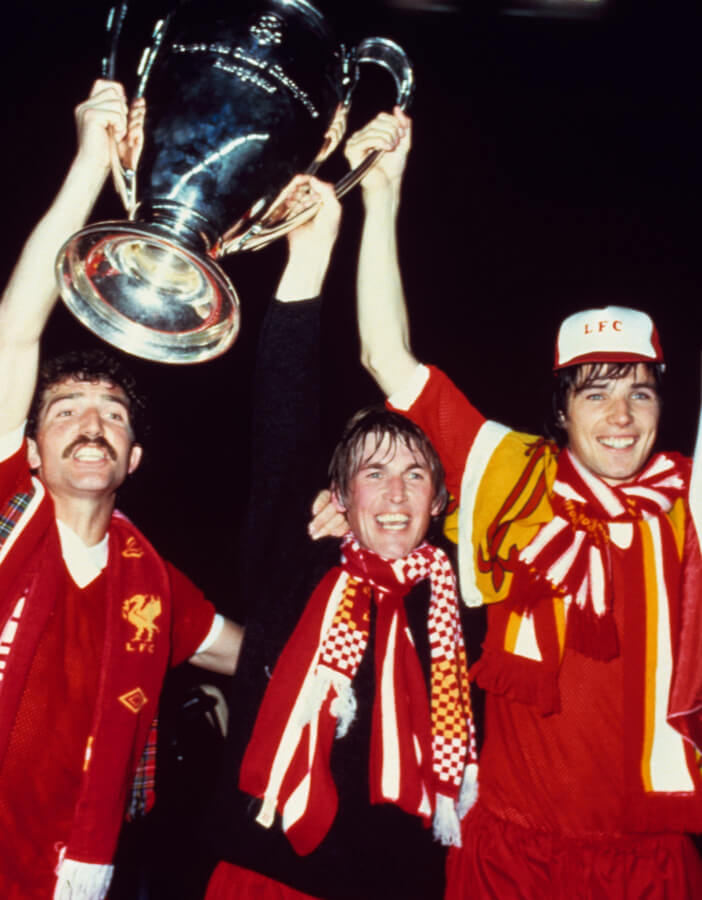

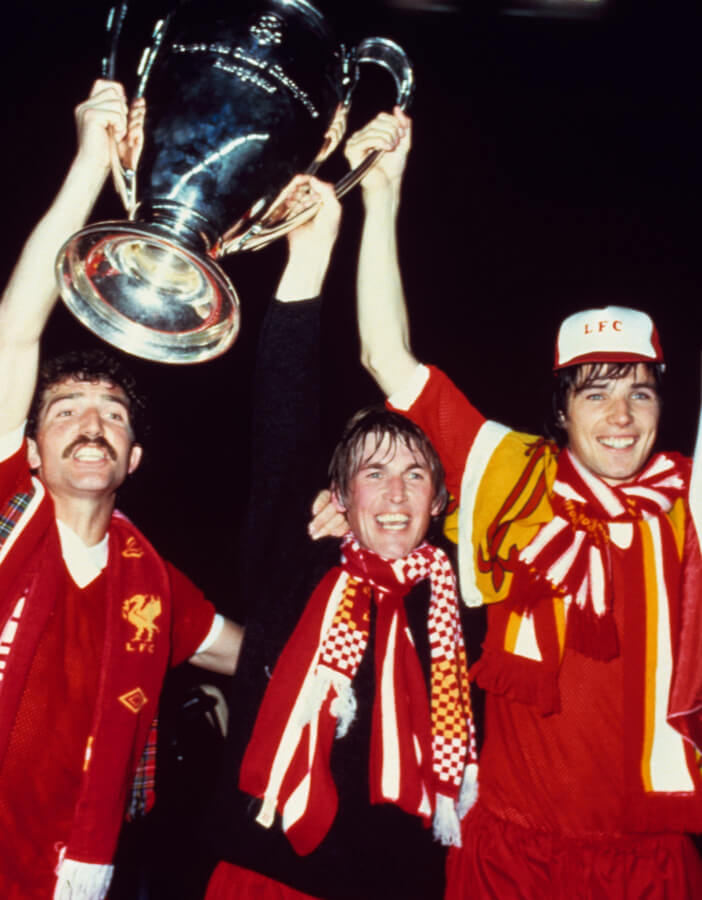

For the football fan, Dalglish’s insights into his first European Cup final victory in 1978 are revelatory. The Liverpool ace scored the only goal against Club Brugge, and he explains how he studied opposition keeper Birger Jensen, noticed how he went down early on shots and dinked the ball over him for the winner. Observation, analysis, execution. Highlights throughout show Dalglish to have been among the best of all time with his back to goal, a key feature of his telepathic partnership with Ian Rush. A gem of a clip has George Best echoing the point: “Kenny was always three or four moves ahead of everyone else.” Indeed, the enchanting footage of his glory years makes you wonder how Dalglish never won the Ballon d’Or.

The film skilfully weaves the personal and universal, no more so than when Dalglish is pictured in 1985, having been appointed as Reds player-manager the day after the Heysel Stadium disaster, when 39 mostly Juventus fans died ahead of the European Cup final against Liverpool. Tragedy was to return again in 1989, and the film deals deftly and delicately with the Hillsborough disaster that took the lives of 97 Liverpool supporters. The pace slows. The story of how Dalglish’s son Paul was for a time among those missing is harrowing, and a stark, still image captures Dalglish looking across the pitch as the horror unfolds.

We see Dalglish the parent, the player, the manager, the ambassador on repeat in suit and thin black tie at funeral after funeral. “I wouldn’t change what I did,” he explains. “There was no way we were going to step back and not be as helpful as we possibly could. It was our turn to be their supporters.”

The film is clear that the impact of Hillsborough led to Dalglish’s shock resignation from Liverpool in 1991. As his wife Marina tells it, “Hillsborough really, really hit Kenny. He wasn’t himself. I knew there was something not right with him. In his heart, he didn’t want to leave, but he felt he had to.”

The film ends there, not dealing with his later Premier League title triumph with Blackburn Rovers nor his return to Liverpool – the story of a man of genius and a man of character already told.

He was Glasgow’s. He is Liverpool’s. Now he can be the world’s. Kenny Dalglish, the captivating new documentary by Asif Kapadia – the Oscar and Bafta-winning director of Senna, Amy and Diego Maradona – introduces the Celtic, Liverpool and Scotland legend to a new audience, telling a story of talent, loyalty and community.

Kapadia relates this tale with his trademark use of archive footage. There are no talking heads or omniscient narrators, with most of the commentary coming from Dalglish himself, his wife Marina or his former Liverpool team-mates Alan Hansen and Graeme Souness. The fresh imagery – and the filmmaker unearthed 100 film reels alone from Dalglish’s Celtic days – makes the past present. Those early Celtic clips show better than any how supremely gifted Dalglish was. His anticipation, feints and touches display a mastery of timing and space; some of his movements resemble Lionel Messi before his time.

The film deals breezily with Dalglish’s childhood, followed by the Celtic era and his first Old Firm goal against Rangers. “That was the big ’un,” he says. “Not because it was a great goal. Because it can set your life up for you.” Life-changing too is his wedding as a Protestant player for a largely Catholic-supported team to his Catholic wife Marina (“the best signing I ever made”). The clips highlight Dalglish the man: his refusal to leave Celtic when manager Jock Stein suffered a car accident, the so-called “Jock Mafia” he formed with Hansen and Souness at Anfield, and Christmas Day with his family.

For the football fan, Dalglish’s insights into his first European Cup final victory in 1978 are revelatory. The Liverpool ace scored the only goal against Club Brugge, and he explains how he studied opposition keeper Birger Jensen, noticed how he went down early on shots and dinked the ball over him for the winner. Observation, analysis, execution. Highlights throughout show Dalglish to have been among the best of all time with his back to goal, a key feature of his telepathic partnership with Ian Rush. A gem of a clip has George Best echoing the point: “Kenny was always three or four moves ahead of everyone else.” Indeed, the enchanting footage of his glory years makes you wonder how Dalglish never won the Ballon d’Or.

The film skilfully weaves the personal and universal, no more so than when Dalglish is pictured in 1985, having been appointed as Reds player-manager the day after the Heysel Stadium disaster, when 39 mostly Juventus fans died ahead of the European Cup final against Liverpool. Tragedy was to return again in 1989, and the film deals deftly and delicately with the Hillsborough disaster that took the lives of 97 Liverpool supporters. The pace slows. The story of how Dalglish’s son Paul was for a time among those missing is harrowing, and a stark, still image captures Dalglish looking across the pitch as the horror unfolds.

We see Dalglish the parent, the player, the manager, the ambassador on repeat in suit and thin black tie at funeral after funeral. “I wouldn’t change what I did,” he explains. “There was no way we were going to step back and not be as helpful as we possibly could. It was our turn to be their supporters.”

The film is clear that the impact of Hillsborough led to Dalglish’s shock resignation from Liverpool in 1991. As his wife Marina tells it, “Hillsborough really, really hit Kenny. He wasn’t himself. I knew there was something not right with him. In his heart, he didn’t want to leave, but he felt he had to.”

The film ends there, not dealing with his later Premier League title triumph with Blackburn Rovers nor his return to Liverpool – the story of a man of genius and a man of character already told.

He was Glasgow’s. He is Liverpool’s. Now he can be the world’s. Kenny Dalglish, the captivating new documentary by Asif Kapadia – the Oscar and Bafta-winning director of Senna, Amy and Diego Maradona – introduces the Celtic, Liverpool and Scotland legend to a new audience, telling a story of talent, loyalty and community.

Kapadia relates this tale with his trademark use of archive footage. There are no talking heads or omniscient narrators, with most of the commentary coming from Dalglish himself, his wife Marina or his former Liverpool team-mates Alan Hansen and Graeme Souness. The fresh imagery – and the filmmaker unearthed 100 film reels alone from Dalglish’s Celtic days – makes the past present. Those early Celtic clips show better than any how supremely gifted Dalglish was. His anticipation, feints and touches display a mastery of timing and space; some of his movements resemble Lionel Messi before his time.

The film deals breezily with Dalglish’s childhood, followed by the Celtic era and his first Old Firm goal against Rangers. “That was the big ’un,” he says. “Not because it was a great goal. Because it can set your life up for you.” Life-changing too is his wedding as a Protestant player for a largely Catholic-supported team to his Catholic wife Marina (“the best signing I ever made”). The clips highlight Dalglish the man: his refusal to leave Celtic when manager Jock Stein suffered a car accident, the so-called “Jock Mafia” he formed with Hansen and Souness at Anfield, and Christmas Day with his family.

For the football fan, Dalglish’s insights into his first European Cup final victory in 1978 are revelatory. The Liverpool ace scored the only goal against Club Brugge, and he explains how he studied opposition keeper Birger Jensen, noticed how he went down early on shots and dinked the ball over him for the winner. Observation, analysis, execution. Highlights throughout show Dalglish to have been among the best of all time with his back to goal, a key feature of his telepathic partnership with Ian Rush. A gem of a clip has George Best echoing the point: “Kenny was always three or four moves ahead of everyone else.” Indeed, the enchanting footage of his glory years makes you wonder how Dalglish never won the Ballon d’Or.

The film skilfully weaves the personal and universal, no more so than when Dalglish is pictured in 1985, having been appointed as Reds player-manager the day after the Heysel Stadium disaster, when 39 mostly Juventus fans died ahead of the European Cup final against Liverpool. Tragedy was to return again in 1989, and the film deals deftly and delicately with the Hillsborough disaster that took the lives of 97 Liverpool supporters. The pace slows. The story of how Dalglish’s son Paul was for a time among those missing is harrowing, and a stark, still image captures Dalglish looking across the pitch as the horror unfolds.

We see Dalglish the parent, the player, the manager, the ambassador on repeat in suit and thin black tie at funeral after funeral. “I wouldn’t change what I did,” he explains. “There was no way we were going to step back and not be as helpful as we possibly could. It was our turn to be their supporters.”

The film is clear that the impact of Hillsborough led to Dalglish’s shock resignation from Liverpool in 1991. As his wife Marina tells it, “Hillsborough really, really hit Kenny. He wasn’t himself. I knew there was something not right with him. In his heart, he didn’t want to leave, but he felt he had to.”

The film ends there, not dealing with his later Premier League title triumph with Blackburn Rovers nor his return to Liverpool – the story of a man of genius and a man of character already told.

He was Glasgow’s. He is Liverpool’s. Now he can be the world’s. Kenny Dalglish, the captivating new documentary by Asif Kapadia – the Oscar and Bafta-winning director of Senna, Amy and Diego Maradona – introduces the Celtic, Liverpool and Scotland legend to a new audience, telling a story of talent, loyalty and community.

Kapadia relates this tale with his trademark use of archive footage. There are no talking heads or omniscient narrators, with most of the commentary coming from Dalglish himself, his wife Marina or his former Liverpool team-mates Alan Hansen and Graeme Souness. The fresh imagery – and the filmmaker unearthed 100 film reels alone from Dalglish’s Celtic days – makes the past present. Those early Celtic clips show better than any how supremely gifted Dalglish was. His anticipation, feints and touches display a mastery of timing and space; some of his movements resemble Lionel Messi before his time.

The film deals breezily with Dalglish’s childhood, followed by the Celtic era and his first Old Firm goal against Rangers. “That was the big ’un,” he says. “Not because it was a great goal. Because it can set your life up for you.” Life-changing too is his wedding as a Protestant player for a largely Catholic-supported team to his Catholic wife Marina (“the best signing I ever made”). The clips highlight Dalglish the man: his refusal to leave Celtic when manager Jock Stein suffered a car accident, the so-called “Jock Mafia” he formed with Hansen and Souness at Anfield, and Christmas Day with his family.

For the football fan, Dalglish’s insights into his first European Cup final victory in 1978 are revelatory. The Liverpool ace scored the only goal against Club Brugge, and he explains how he studied opposition keeper Birger Jensen, noticed how he went down early on shots and dinked the ball over him for the winner. Observation, analysis, execution. Highlights throughout show Dalglish to have been among the best of all time with his back to goal, a key feature of his telepathic partnership with Ian Rush. A gem of a clip has George Best echoing the point: “Kenny was always three or four moves ahead of everyone else.” Indeed, the enchanting footage of his glory years makes you wonder how Dalglish never won the Ballon d’Or.

The film skilfully weaves the personal and universal, no more so than when Dalglish is pictured in 1985, having been appointed as Reds player-manager the day after the Heysel Stadium disaster, when 39 mostly Juventus fans died ahead of the European Cup final against Liverpool. Tragedy was to return again in 1989, and the film deals deftly and delicately with the Hillsborough disaster that took the lives of 97 Liverpool supporters. The pace slows. The story of how Dalglish’s son Paul was for a time among those missing is harrowing, and a stark, still image captures Dalglish looking across the pitch as the horror unfolds.

We see Dalglish the parent, the player, the manager, the ambassador on repeat in suit and thin black tie at funeral after funeral. “I wouldn’t change what I did,” he explains. “There was no way we were going to step back and not be as helpful as we possibly could. It was our turn to be their supporters.”

The film is clear that the impact of Hillsborough led to Dalglish’s shock resignation from Liverpool in 1991. As his wife Marina tells it, “Hillsborough really, really hit Kenny. He wasn’t himself. I knew there was something not right with him. In his heart, he didn’t want to leave, but he felt he had to.”

The film ends there, not dealing with his later Premier League title triumph with Blackburn Rovers nor his return to Liverpool – the story of a man of genius and a man of character already told.

He was Glasgow’s. He is Liverpool’s. Now he can be the world’s. Kenny Dalglish, the captivating new documentary by Asif Kapadia – the Oscar and Bafta-winning director of Senna, Amy and Diego Maradona – introduces the Celtic, Liverpool and Scotland legend to a new audience, telling a story of talent, loyalty and community.

Kapadia relates this tale with his trademark use of archive footage. There are no talking heads or omniscient narrators, with most of the commentary coming from Dalglish himself, his wife Marina or his former Liverpool team-mates Alan Hansen and Graeme Souness. The fresh imagery – and the filmmaker unearthed 100 film reels alone from Dalglish’s Celtic days – makes the past present. Those early Celtic clips show better than any how supremely gifted Dalglish was. His anticipation, feints and touches display a mastery of timing and space; some of his movements resemble Lionel Messi before his time.

The film deals breezily with Dalglish’s childhood, followed by the Celtic era and his first Old Firm goal against Rangers. “That was the big ’un,” he says. “Not because it was a great goal. Because it can set your life up for you.” Life-changing too is his wedding as a Protestant player for a largely Catholic-supported team to his Catholic wife Marina (“the best signing I ever made”). The clips highlight Dalglish the man: his refusal to leave Celtic when manager Jock Stein suffered a car accident, the so-called “Jock Mafia” he formed with Hansen and Souness at Anfield, and Christmas Day with his family.

For the football fan, Dalglish’s insights into his first European Cup final victory in 1978 are revelatory. The Liverpool ace scored the only goal against Club Brugge, and he explains how he studied opposition keeper Birger Jensen, noticed how he went down early on shots and dinked the ball over him for the winner. Observation, analysis, execution. Highlights throughout show Dalglish to have been among the best of all time with his back to goal, a key feature of his telepathic partnership with Ian Rush. A gem of a clip has George Best echoing the point: “Kenny was always three or four moves ahead of everyone else.” Indeed, the enchanting footage of his glory years makes you wonder how Dalglish never won the Ballon d’Or.

The film skilfully weaves the personal and universal, no more so than when Dalglish is pictured in 1985, having been appointed as Reds player-manager the day after the Heysel Stadium disaster, when 39 mostly Juventus fans died ahead of the European Cup final against Liverpool. Tragedy was to return again in 1989, and the film deals deftly and delicately with the Hillsborough disaster that took the lives of 97 Liverpool supporters. The pace slows. The story of how Dalglish’s son Paul was for a time among those missing is harrowing, and a stark, still image captures Dalglish looking across the pitch as the horror unfolds.

We see Dalglish the parent, the player, the manager, the ambassador on repeat in suit and thin black tie at funeral after funeral. “I wouldn’t change what I did,” he explains. “There was no way we were going to step back and not be as helpful as we possibly could. It was our turn to be their supporters.”

The film is clear that the impact of Hillsborough led to Dalglish’s shock resignation from Liverpool in 1991. As his wife Marina tells it, “Hillsborough really, really hit Kenny. He wasn’t himself. I knew there was something not right with him. In his heart, he didn’t want to leave, but he felt he had to.”

The film ends there, not dealing with his later Premier League title triumph with Blackburn Rovers nor his return to Liverpool – the story of a man of genius and a man of character already told.

He was Glasgow’s. He is Liverpool’s. Now he can be the world’s. Kenny Dalglish, the captivating new documentary by Asif Kapadia – the Oscar and Bafta-winning director of Senna, Amy and Diego Maradona – introduces the Celtic, Liverpool and Scotland legend to a new audience, telling a story of talent, loyalty and community.

Kapadia relates this tale with his trademark use of archive footage. There are no talking heads or omniscient narrators, with most of the commentary coming from Dalglish himself, his wife Marina or his former Liverpool team-mates Alan Hansen and Graeme Souness. The fresh imagery – and the filmmaker unearthed 100 film reels alone from Dalglish’s Celtic days – makes the past present. Those early Celtic clips show better than any how supremely gifted Dalglish was. His anticipation, feints and touches display a mastery of timing and space; some of his movements resemble Lionel Messi before his time.

The film deals breezily with Dalglish’s childhood, followed by the Celtic era and his first Old Firm goal against Rangers. “That was the big ’un,” he says. “Not because it was a great goal. Because it can set your life up for you.” Life-changing too is his wedding as a Protestant player for a largely Catholic-supported team to his Catholic wife Marina (“the best signing I ever made”). The clips highlight Dalglish the man: his refusal to leave Celtic when manager Jock Stein suffered a car accident, the so-called “Jock Mafia” he formed with Hansen and Souness at Anfield, and Christmas Day with his family.

For the football fan, Dalglish’s insights into his first European Cup final victory in 1978 are revelatory. The Liverpool ace scored the only goal against Club Brugge, and he explains how he studied opposition keeper Birger Jensen, noticed how he went down early on shots and dinked the ball over him for the winner. Observation, analysis, execution. Highlights throughout show Dalglish to have been among the best of all time with his back to goal, a key feature of his telepathic partnership with Ian Rush. A gem of a clip has George Best echoing the point: “Kenny was always three or four moves ahead of everyone else.” Indeed, the enchanting footage of his glory years makes you wonder how Dalglish never won the Ballon d’Or.

The film skilfully weaves the personal and universal, no more so than when Dalglish is pictured in 1985, having been appointed as Reds player-manager the day after the Heysel Stadium disaster, when 39 mostly Juventus fans died ahead of the European Cup final against Liverpool. Tragedy was to return again in 1989, and the film deals deftly and delicately with the Hillsborough disaster that took the lives of 97 Liverpool supporters. The pace slows. The story of how Dalglish’s son Paul was for a time among those missing is harrowing, and a stark, still image captures Dalglish looking across the pitch as the horror unfolds.

We see Dalglish the parent, the player, the manager, the ambassador on repeat in suit and thin black tie at funeral after funeral. “I wouldn’t change what I did,” he explains. “There was no way we were going to step back and not be as helpful as we possibly could. It was our turn to be their supporters.”

The film is clear that the impact of Hillsborough led to Dalglish’s shock resignation from Liverpool in 1991. As his wife Marina tells it, “Hillsborough really, really hit Kenny. He wasn’t himself. I knew there was something not right with him. In his heart, he didn’t want to leave, but he felt he had to.”

The film ends there, not dealing with his later Premier League title triumph with Blackburn Rovers nor his return to Liverpool – the story of a man of genius and a man of character already told.